UnBooks:The Old Man and LV

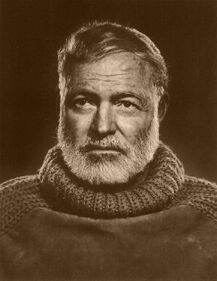

My Dad resembles author Ernest Hemingway, and he plays it for all it's worth. He's shaped his white beard and cut his hair to look more like the writer, who hardly anyone under thirty recalls or reads nowadays. Dad's been married four times, just like the worldly Hemingway. But that has to be coincidence. He once even ran with the bulls to prove to himself that he was a man, unlike Hemingway, who had to prove that he was a man each morning before pouring his first hair of the dog. And Dad hasn't had his share of electro-shock treatments and shot his head off. Yet.

So I'm usually not surprised when he has a rush of energy and, like Ernest Hemingway, makes a snap decision in the direction of adventure.

I remember the phone call like it was yesterday (it was last Friday, around noon). Dad called me at my gallery, Manilow's. "Manny," he said, "we're going to Vegas. Yes, Las Vegas, right now. While the sun is still shining. I want to see the sun on lots of windows. To see it light them up, like little suns."

For years I've been trying to get Dad to Vegas for a father-son playdate. I'd been several times, and knew what fun it was and how much Dad would enjoy it. But he always had an excuse at the ready. He had a business meeting, or he and his buddies were going to the game, or he was dating yet another neighbor woman who was angling to be his "one for the thumb" - although it usually ended up the other way around. Dad's best excuse was that he had to sit around and watch the grass grow. I thought that one was pretty lame until I went by the old house and found that he had set up a grow room.

Dad had already gotten us plane tickets and booked a suite at the Luxor. So, shaking my head at the lunacy, I rushed home to pack a bag and asked a neighbor boy to pick up the Kansas City Star from my front porch. Even though I live in Madison, Wisconsin, Dad insists that I keep a subscription to the Star - "News from afar travels like smoke," he'd say, "mists of printer's ink populated by thousand-yard stares." I then drove to Chicago to meet him, and got there just about the time we were to board.

I hadn't seen dad in several months, and he looked good, "like an owl lean on fast rodents" - one of his favorites. He looked me over, like he does when we've been separated for awhile. He nodded his approval, gave me a bear hug, and then we were off.

"Welcome to Las Vegas"

The approach to Vegas is spectacular. Coming in low, from the plane's window the Sierra Madre mountains and their foothills splash orange, red, and purple onto the eyes' palette in just the right combination to remember forever. The city then emerges unexpectedly from this geological plumage (as if only Vegas has the power to alter such a landscape). Dad leaned his elbow on the tiny plastic window sill and looked out the window during most of the flight, as was his custom. "We're ground dwellers by nature," he'd tell his seatmates, not turning to look at them as he spoke, "so when I get into the air I like to know it." But he did the unexpected, and leaned back and closed his eyes as we cleared the approach over the mountain and were upon Vegas.

"I want to take this one in in large gulps," was all I heard him say. Knowing that dad doesn't like to watch movie previews, and always sits in the second row of a theater - "Near the action. Where the herd drops away." - I understood what he was doing.

He kept his eyes closed until we landed and then walked like a blind man so as not to catch a glimpse of the gambling den that is Vegas International Airport. We got into a cab, and an hour later were dropped off at the Luxor Hotel, a four minute ride from the terminal. I chalked it up to experience, paid the piper, and duct-taped my wallet to the inside of my pocket.

The Luxor is in the shape of the Great Pyramid of Giza. It's probably two or three times the size of that pyramid. Dad had shut his eyes for the entire time in the cab, spending half of it napping and half of it telling the cabdriver about the madwomen of Paris and their absinthe green eyes, so when we walked into the Luxor's lobby he got his first real look at the perpetually flowering plant that is Las Vegas.

Dad paused for just a moment, then hurried past the large Egyptian statues in the lobby and arrived at the casino's entrance, a stone's throw from the door. He stopped just outside the casino's entrance. He took in a few deep breaths - as he learned to do when he fished the gulf - then spent a minute standing totally still except for his eyes, which were observing the wildlife in their den. "Sodom and Gomorrah lit by modern lighting," he finally said. "Can you sense the edge? Madness here, a panic unleashed to run its course. Lead on, son."

We picked up our bags, Dad paid a guy for no reason, and we checked-in and went up to our room. Dad took a shower as I unpacked, we changed places, and when I came out of the john we were packed again. Dad had a look in his eye, it had shifted for him, and we went downstairs.

The hours run together

The next twelve hours are a blur. After a stop at the bar, buying a few for a hooker too young to gamble, and singing harmonies with the bartender and a guy dressed like a Geisha, Dad and I entered the casino. He immediately went to town.

Big wads of cash flew out of his pockets. He must have been saving it up for years. The wads landed on the craps table, the roulette wheel, the pristine green tumult of the blackjack pit. Scantily clad women, but no scantily clad men, took our drink orders and brought us free booze - expecting nothing more in return than a courtesy tip to keep them jumping. We were already drunk as otters, and matched each other drink for drink, a game we'd played since I was a kid.

Both Dad and I won some money, turned around and gave it back, won again, and we were pretty much even when Dad finally decided to leave the tables and work the slots. "Slot machines are solitary silos," Dad said. "All lights and noise, little else in way of sustenance." This time I didn't know what the hell he was talking about. I was drunk enough to howl at the moon, and faintly remember stumbling outside and doing so. I don't like the slots. There's no challenge in them. But they got Dad's attention, and he started to prime them with good money. First he played the penny slots, just to touch the hem. After awhile he moved up to the nickels, then skipped the quarter machines entirely and went right to the dollars.

He lost. Not a flashing light or a cartoon sound came from any of his machines. Not one red bucking cowboy twirling lassos amid layers of ducks ridden by witches licking cauldron born candy canes lined up on the screen. Nothing.

A half hour, and then another, went by like slow freight. I brought Dad some food, and talked to him about Sammy Sosa and his home runs. Dad looked at me then, with a quizzical expression on his face - the far-away look of one who has seen perfection which has yet to register. Crowds gathered tight in around him, for the lore of going on such a magnificent losing streak attracts the same type of loner or borderline personality disordered onlooker who stands and cheers a win streak like they'd cheer a fat guy threatening to jump off a roof. Winning streak, losing streak, there is no difference. It's all in the being there when "something different" happens.

A few minutes later, still without a win - not even a bite - Dad actually upped his loses by moving to the five dollar machines. By this time the liquor hostesses were bringing us so many drinks that I spilled a few without knowing it. My pants were soaked and dripping olives, but I was too drunk to care. Dad played, and played again. At the eighty minute mark, nothing. A few more minutes, the same. I spilled another drink, and may have tried to drink it from the floor. Then at what I later heard was the 84 minute mark, Dad quickly moved to the monster, the $100 slot. He played there for a minute, lost another five hundred, and tried again. This time, as the lights and whistles and floating ghosts flipped around in the machine, peppermint drops amid whirling dervishes and dizzy wiccans, suddenly all hell broke loose. For two whole minutes the slot gave off rainbows and sounds like "an ocean racing hard against the shore," Dad later recalled. The machine seemed to shake in his hand - "To touch me well," he told me, "to draw blood" - but he held on until it subsided.

We have a winner!

He'd won. Dad had won big. A pit boss elbowed his way through the crowd, looked at the machine, shook his head in disbelief, and told Dad he'd just won $15 million dollars. It was by far one of the largest slot wins in Vegas history. The Luxor president was called to the floor, security guards surrounded Dad, and professional technicians arrived to examine the gaming device to confirm that the payoff was legit. Only then, after what seemed like a lifetime but must have been closer to 15 minutes, did the hotel administrator and Carrot Top shake Dad's hand, pat him on the back, and hand him his check. Dad then did something so unexpected that he surprised even me, and I've seen him wrestle women with his hands and their legs tied-behind his back. He wanted the money in cash. $15 million, in $10s, $20s and $50s, thank you very much. With a few dozen tens and fives in there for easy spending.

Luxor's manager and his casino bosses had a brief sit-down, called Dad over to ascertain if he was serious, and I heard them tell him that they'd have to report his winnings to the IRS and the Nevada Gaming Commission. From what I could tell from 20 feet away, apart from that there was no reason he couldn't have his money exactly as he wanted it. After they talked for another few minutes, it came. Stacks and stacks of tens and twenties and fifties, piled high on a craps table, the cash finally filling four very large dufflebags. Dad lashed the dufflebags together so he could carry them, and hoisted them onto his back. The bags were huge - they looked like old army dufflebags that someone from the hotel had kept in his office since Nam - and the leather-like dark green skin moved a little with each step Dad took, the stacks of money settling their weight inside. I, of course, offered to help, but Dad just looked at me. "Few know the weight of their life," he said. "I now feel my worth here, in my spine, and on my shoulders. A man blessed with this knowledge carries it alone."

OK Dad, jeez. Now he was taking the drama too far. What was I supposed to do, play the dutiful little boy and follow him - my father's back weighed down with his victory and new lot in life not unlike a white-haired silverback mangod on his way to Calvary - up to his room? But then, Lord have mercy, instead of heading for the elevators, Dad started to walk out the door!

Dad walks down the strip

By the time we turned left onto the Vegas strip the people in the crowd who'd watched Dad's record-breaking losing streak, and then his extraordinary win, had stirred from their glassy-eyed boozed induced observational haze, and were following us. One after the other, and then together, they told Dad why they wanted some of his money. "My girlfriend, she wants jewelry and, you know, a nice car - I can't afford that!" "I'm going to lose my house mister, twenty years I've worked like a dog..." "My Mom's gotta eat something other than table scraps, c'mon buddy." "I invented a perpetual motion machine, see, I've got it right here, in a compartment in my teeth, but the funding dried-up." The problems and desires and moronic babblings poured out of these people like lizards squirming for elbow room on the best flat rock. Then as more strangers on the strip heard what had happened they joined the swarming menangerie. A few of the larger ones pushed against Dad and grabbed at the canvas of the duffle bags to test their give.

We pushed our way through them and kept walking. As we crossed a bridge we passed a homeless man with a sign saying that he just wanted some money for a beer. Dad gave him a thumbs up and invited him to join us. Three drunken college boys tried to heckle Dad, calling him a jellyfish wrangler. I had no idea what that meant, but I knew what to do next. "Dad, let's go inside," I said as we neared the MGM Grand, "I'm guessing we need a drink." His eyes lit up like Christmas morning, as did those of the homeless man and the college boys, and we all went in.

The lions lounging in the massive cage in the Grand's sprawling lobby spotted Dad and his heavy bags. They arose quickly, and hurried to hide. Dad saw this, and I think it bothered him. When we and his followers had finished our refreshments, and then gave in to a bet from a European and had another, I tried to talk Dad into stopping. "C'mon, let's grab a cab back to the Luxor. Or to a bank or something." But he just smiled that charming-Dad smile. "No, son," he said. "I walk to review my life. To redeem it. In the open. Among the people. Alone with my uncertainties within these rolling waves of humanity." And with his fourth glass of Sazerac nestled comfortably in his hand, a growl of a she-lion echoing in the tequila-salted air, and an attempted police escort told to sod off and leave us the fuck alone, he made his way to the door and towards the heart of the strip.

We walked like this for over a mile. Somewhere along the way the waves of humanity began to be a dick and really started pushing. Dad began to fend them off. He swung his free hand and shoved some of them away, and actually may have slightly wounded a few as they fell into passing traffic. Then one of the duffel bags tore, and, as the rip got larger, the people started grabbing stacks of twenties and fifties, grabbing them and running off. Dad swung harder and hit a few on their snouts, but when I tried to help him protect the money that was now leaking away faster and faster from the hole in the bag's side, he waved me off. "Step away. This is my fight. My timeless stand."

Fight? Timeless stand?? A walk to review his life??? I started to worry about Dad's emotional state, and as I saw that all of the money in the first dufflebag was gone and the bag itself hung among the three others like empty skin, we continued walking. Dad was counting his steps out loud now. We walked this way for a long time. And while it became easier with practice to beat back a single scavenger or hanger-on, when the greedy crowd started to surge towards us again I got behind Dad and pushed, pushed him hard, into the next door we passed. It happened to be the colorful corner entrance to the Paris Hotel.

I looked back over my shoulder, saw the surge of the starving, and called over a few of the Parisian security guards. I filled them in on the situation. They formed a ring around us, comped us two suites and a lunch buffet, and handled the crowd with little damage to themselves. We sat down in the casino - all entrances to Paris lead to the casino - to rest our bones and size up the climate. Dad played craps for an hour or so, and won a few grand. He then lost that at roulette. "Roulette reminds me of freezing rain," Dad said, "A bad turn of the wheel and the wires fail, and you have to keep the freezer closed lest cold air seeps out." I told him to shut the fuck up, but he either didn't hear me or didn't care, and kept talking to himself and to the Parisians who fetched our drinks.

"Come here daughter"

Then, inevitably, came the women. There were hookers and barmaids and women who drove over from Utah. The Asians, and English and black goddesses from Jamaica. All the scent from the hotel gathered around Dad, who was now holding court in Paris, as of old.

"Paris, a lifetime of memories before the sun rises, our local star preparing to heat what has stirred in the eve," Dad whispered into the ear of a sultry redhead who looked at him like he was batty, then shrugged and smiled a thousand-watt smile. One thirty-something spotted me nursing a scotch, and asked me who I was. "His son," I answered. She glanced at Dad then, leaned over, and, with a wink in her voice and a tone smooth as velvet draped over satin backed with silk covered in cream, she asked "Can I call you Papa?" "Of course, daughter." And the evening took a turn.

Papa, as they all called him now, showered his women with obscenely expensivechampagne, bought them jewels from one of Vegas's many traveling precious stones salesmen, and when other women sauntered by in designer dresses and two thousand dollar shoes he bought these treasures right off their bodies and gave them to the girls. Did Alice want a Lexus? Here are the keys. Keira, a well-known actress who knew how to talk to men, snuggled up to Papa and called him "Reindeer". A few other women joined the scrum before Dad's inner nature fully emerged and he took them to his suite.

I didn't see him for the next few hours. Sometimes I'd play the tables, but the lighting in Paris' casino is dark, the tables oddly spaced, and the atmosphere not quite right. Wandering the Hotel, exploring its crevices, I eventually grabbed my drinks and took a trip to the top of its faux Eiffel Tower. There the guards had their hands full trying to subdue a goth girl who kept pointing to the sky and shrieking about Santa. But mostly I watched, waited, and drank. I saw Barry Manilow, the sugary singer I was named after who now headlined the entertainment at the hotel, come out of an elevator. I later heard that he'd tried for at least an hour to get into Dad's room, but to no avail. Then, as I felt my head clearing of the alcohol and hurried to refresh my glass, Dad appeared. He was alone. "To blend touch with sinew," he said through his smile, "I dreamt of Cuba when I dozed, which was momentarily at best." Handing him a drink, I noticed that another duffle bag was limp, a third held only half of its former bulk, and only one was still bulging with the green meat of the catch.

The running wild

We ate breakfast, to renew our strength. Dad enjoyed a stack of hotcakes with his rum, and I, eggs, sunny side up, with a shot and a beer to lubricate their departure. As Dad shifted his duffles to keep his balance, I noticed he dribbled just the tiniest spot of syrup onto his shirt, there to rest amongst the other debris of the quest.

We finished eating, downed our third round, and Dad, without a word, hoisted his load and again walked out the door. I understood now that Dad was on what can only be called a journey of the wise king, or stupid chimneysweep, depending on your point of view, understanding of mythology, and gullibility level. I got up grudgingly and followed. We slowly made our way over to Caesar's Palace, and then into the depths of the Forum.

Whatever time of day, the Forum at Caesar's - like Paris' casino or Pan's boudoir - presents perpetual dusk. Its ceiling is painted robin-shell blue to resemble the sky, clouds portrayed by a lighter paint. "What the mind beholds, the temperament puts on as clothing," Dad told a passing group of Scotsmen who, to a man, pretended they didn't hear him.

We meandered deeper into the seemingly never-ending array of high-end shops, stopping every so often for Dad to unload cash. A Mont Blanc pen here, ten Judith Ripka bracelets there, twenty-five pairs of Italian shoes, some to be delivered to our suites at the Luxor, others to our suites at the Paris. The third dufflebag was nearly empty as we skirted around the fountain holding giant statues of Olympian Gods. These eerily-possessed symbols of power move and talk and perform amidst an accompanying laser show. There, lights flashing, thunder echoing, and Gods and Goddesses mechanically moving like 1950s robots and grumbling on about nothing in particular, Dad stopped in his tracks and stared in the other direction like a madman confronted with his illness. He was actually speechless, for the first time I could remember. I unconsciously trembled at what had befallen my father. "Dad, pop, are you okay?" I asked, concerned. A second passed, then another, before he lifted his hand like Lugosi and pointed his finger towards the shops. And there, big as life, scratching his head and looking bored, sat Pete Rose.

My dad loves Pete Rose as much as a man can love another man, outside of the community of course. They were about the same age, and just about the time that Dad was wounded while driving an ambulance in Nam - only to be kicked deeper in his stomach and broken-heart when the nurse's aide he fell in love with in-country sent him a Dear John letter, postage due - Pete Rose was starting to show his greatness with the Cincinnati Reds baseball club. Dad followed Rose in the sports section every day during those last ten seasons, and as Rose climbed to the top of the all-time hit list Dad took pleasure in every record-setting single, each record breaking run scored. Then, when Rose was later charged with betting on baseball during his tenure as Reds manager, Dad scoffed and exclaimed "He did nothing but know the guts of his game." Dad never took any position but at Rose's back, a same-generation hero to the boy and then to the man. Now here was Pete Rose, sitting right in front of us.

Dad regained his composure and his voice, patted me on the back, and said "The day, son, the wondrous day indeed." He walked up to Rose, who I later found out works weekends signing jerseys and posing for pictures at the Sporting Goods store in the Forum. "Mr. Baseball," he said, "the smell of the diamond perfumes this air." Dad then bear hugged the surprised ex-ballplayer. "Yeah, hey, alright, good to meet you too pal. What's with the dufflebags?" "An attempt to boundary life with paper money, the fuel, the scourge, what we seek and what we throw at pleasures and troubles the same." At the mention of money Rose's eyes lit up, and only then did I catch sight of the small television on his table tuned to a horseracing station that I never knew existed. "Sit down, Mister, sit down. Call me Pete." "Honored. You can call me Santiago, or better yet, Papa," and Dad sat.

Well, you can guess the rest. Within an hour, and maybe a few bottles later, the fourth duffle was empty except for the leavings, and Pete Rose was drunkenly cursing his luck and his handicapper. "Son of a bitch, what a fucking streak of bad luck. A five-to-one sure thing he says, 'Bet the boat on this filly's nose, Pete, right on the tippy-tip tip of her nose' the dickhead tells me, and goddammit. Goddammit is all I have to say. Just wasn't in the cards, friend." Dad took it in stride even as I looked crestfallen. "Dad?" "Son, a slice of life. Pete Rose and I almost bested the odds, we shaved those horses close, didn't we now? Pete, you've made my day."

Rose stood up, gave Dad a signed jersey, and abruptly left to get a steak at the Flamingo. Dad's four dufflebags were still strapped onto his back, but they were now deflated, picked almost clean inside, hanging there not by gravity to their self-appointed sun-king but by ropes and knots alone. Dad had a smile on his face as big as all indoors. "Can you believe it, Manny! Pete Rose. Let's go back to Paris and talk of our blind beggar's luck at meeting the most magnificent man in sports."

I slapped my palm to my head so quickly that I actually hurt myself.

All things culminate in bells

Dad met LuLu on the strip on our way back to Paris, and he fell instantly in love. "Thunderstruck," he got down on one knee right there on the cement and told her, "The love, as a wise man wrote, that is instantaneous and irreversible. Follow my joy, which leads to you, my heart - mere muscle transformed to magnificent magnet, a vessel no longer seeking shadowed winding turns, only straight illumined lines."

What probably happened is alcohol poisoning. We'd been hitting the bottle nonstop for about 30 hours, and at the exact moment LuLu staggered up and asked Dad for a light his brain, finally short-circuiting from the "fire within", mistook imminent collapse for affection. Timing is everything, that same wise man wrote, and LuLu's timing was apparently the result of last night's fix.

"Ask not for whom the wedding bell tolls," Dad said while playing the spoons, "They toll for me. And LuLu here."

With the last of his folding money dug from the bottom creases of the bags, Dad hired some goons just because he could, bought LuLu a real Vegas wedding complete with an Elvis impersonator and what may have been the real Wayne Newton, and bought me a long-legged long-necked hooker named Wildflower. Dad and his bride crossed the street from Paris, walked along the ponds left-bank for a few minutes, and then climbed in. Dad and LuLu had the famed Bellagio Fountain all to themselves, and they skinny-dipped, yodeled, and made love in the shallow dancing waters. No one paid them the slightest bit of attention, except the guy portraying Captain Jack Sparrow, one of the locals tourists pay to pose in pictures with them. "Let Sparrow stay," Dad told his goons as they moved towards the mariner, "Deep mysteries abide in him. Come, we will pose with you, Sparrow. Let you be witness to more of life."

"Shiver me timbers," Sparrow giggled as LuLu felt him up. I saw it, but Dad didn't, and I'll never tell. The Captain soon got a far-away look in his eye, then relaxed, and I saw LuLu pick loose paper from Cap's donation jar. Then we all headed back to Paris to sit at coffee, gin, and absinthe in an open air cafe, to lightly reminisce under the painted evening sky, to talk deep into the night about our long day.

Aftermath

I wrote the above account of our Vegas adventure a few days after I got back to my studio, and then tried to forget everything about it. We flew back into O'Hare, and I drove to Madison while dad and LuLu went to his house in Oak Park, the old family home where gramps ate his gun. LuLu told me later that when they got home Papa put his empty duffel bags on the porch as the slack-jawed neighbors stood around on the sidewalk and gawked. One village idiot commented to her peers that the pile of deflated bags made it look like a Vegas casino dweller lived there. LuLu told me that Dad lay down on his old army cot and slept for two days. He awoke only once, to whisper something about dreaming of the ones who got away, the lions who hid from him at the MGM Grand.

I picked up the phone a couple weeks after we got back and spoke to Dad. I told him that I hoped he wasn't feeling too bad about what might have been. "What do you mean, Manny?" "Come on, Dad," - sorry now that I'd broached the subject - "the money. You could have used that money." I'd have heard his laugh across the street, and the phone wasn't on speaker. "What do you take me for, a putz? Yeah, I blew about three million, and had the time of my life. Still got close to twelve million left that those Luxor boys wired to the Cayman Islands account they set up for me. Gave them close to half-a-mil for their trouble, so they wouldn't be too honest with the gentlemen at the IRS."

The last thing I heard on that call was LuLu, laughing like a hyena in the background, mixing the ice for some kind of exotic tropical drink. The clinking of the ice, for some reason, reminded me of my youth in Africa, and of our friend Jack Sparrow, both posing forever in absurd proximity under our local star, the sun.

| Featured version: 9 March 2011 | |

| This article has been featured on the main page. — You can vote for or nominate your favourite articles at Uncyclopedia:VFH. | |